deutsch

english

Paravent ist eine Videoausstellung, die über extraktiven Kapitalismus, verführerische Fake News, Erinnerungen aus der Zukunft, abgelegene militarisierte Küstenlandschaften, queere Sexualität und Liebe erzählt.

Mit Filmen von TJ Cuthand, Matthew Arthur Williams, Andrew Black, Maxim Franks & Alice Escher und einem Paravent sowie anderen nutzbaren Objekten von Anna Kaufmann, Nele Lübbert, Antonia Breme & Martin Flemming. Der Paravent wird von Katja Stoye-Cetin's Arbeiten ergänzt.

Paravent is a video exhibition that tells about extractive capitalism, seductive fake news, memories from the future, remote militarized coastal landscapes, queer sexuality and love. With works by TJ Cuthand, Matthew Arthur Williams, Andrew Black, Maxim Franks & Alice Escher and a paravent as well as other usable objects by Anna Kaufmann, Nele Lübbert, Antonia Breme & Martin Flemming. The Paravent is extended by Katja Stoye-Cetin's works.

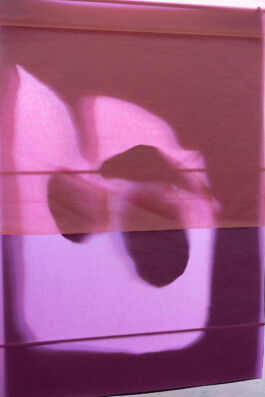

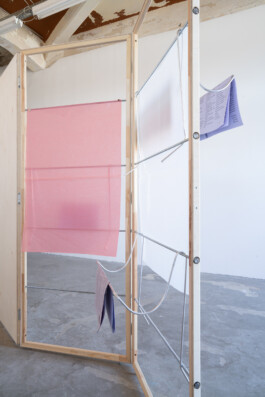

[Bildbeschreibung: Foto Dokumentation von Paravent: In einem großen Raum stehen mehrere Paravents. Manche offen, manche geschlossen. Sie sind aus Holz und werden von Gewindestangen in Form gehalten. In den offenen Paravents hängen rosa Buntpapier Scherenschnitte und Magazinhalter aus Aluminium Rohr. Auf ihnen hängen lilane Skripte der Videos. Zwei Bildschirme hängen über Eck an der Wand. auf ihnen fünf verschiedene Videos. Zwischen ihnen steht ein blauer gedrechselter Kopfhörerhalter. Eine Lampe aus armierungsstahl und Funier, sieht aus als würde sie durch den Raum laufen. Im Hintergrund eine Tür nach draussen, eine Rampe, ein Tisch mit Stühlen, Eine Bar.]

[Image description: Photo documentation of paravent: There are several paravents in a large room. Some open, some closed. They are made of wood and are held in shape by threaded rods. Pink colored paper silhouettes and magazine holders made of aluminum tubing hang in the open screens. Purple scripts of the videos hang on them. Two screens hang across the corner on the wall. on them five different videos. Between them is a turned blue headphone holder. A lamp made out of reinforcment rods and veneer, looks like it is walking through the space. In the background a door to the outside, a ramp, a table with chairs, a bar.]

The paravent is an object that keeps out the wind, creates a space in which the air stands still and that shelters from stares. The paravent has a double function In the exhibition, it marks a space within a communal room, separates and emphasizes at the same time. It also exists in a permeable form, as an element that shows the space behind it and through displaying multilingual transcripts, by which it opens up access points to the video works on display. Silhouettes by artist Katja Stoye-Çetin hang from a paravent, transporting possible shadows from behind the walls to the foreground.

The paravents are infinitely more delicate than some of the divisions we encounter in the video works: the thick glass panes of aquariums, the relentlessly thick glass panes of the jars under which moths and flies are trapped, the wall that surrounds the enclosure of fighting rams, or British Navy nuclear submarines off the Scottish coast.

But when Orpheus begins to sing, the animals stop fighting. A myth and image Herbert Marcuse uses to refer to the transcending powers of the arts1. By reordering what is, the arts are able to create a utopian, a transcending moment that points beyond the world that is, to what could be. Through the array of means used in the video works shown in the exhibition, senses are invigorated that can be used to see, to listen, to feel, and to be.

1 Marcuse, Herbert: Konterevolution und Revolte, Frankfurt a.M. 1973, p. 112.

In the two words Revenge Fantasy, the title of Andrew Black's video work contradictions are already condensed: the fantasy, the imaginary is connected with the word revenge, an in patriarchal-capitalist logic, controlled desire. The video consists of condensed compositions of still and moving image, writing, drawing, voice-over, music and sounds. Shots of the coast and landscape are layered with shots of leaves and sticks being blown out of the image. The stream of thoughts and sensations that is superimposed over the image, in writing and sound, create situations of the self embedded inside the landscape: undressing in nature, spreading the bum cheeks, exposing oneself to the wind and ticks. Other images show care for others (feeding domesticated animals, for example) and oneself (removing a tick from the lower eyelid with the help of others). The affect that the tick triggers in one of the people present ("Kill it! Kill it!) anticipates the names of the eluding, yet present, British Navy nuclear warships. They bear the names of controlled needs, of spectacle: revenge, repulse, vanguard and vengeance. And the language in the video also changes, becoming pejorative and hurtful (toward gay sexuality and intimacy, for example). But the last image in the video shows a person on the shore gently adjusting a shot with the camera - pointing to the possibility of the worlds transformation through art.

TJ Cuthand's video work Extractions is about the extraction of raw materials and the destruction of environment and society. The filmmaker's reflective and questioning, revealing and vulnerable voice-over describes the destruction of indigenous communities and livelihoods through the historical and ongoing colonization of land and people. He also addresses the ambivalent interconnectedness between indigenous people and settlers: Indigenous populations sell land back to white settler companies, which build mines on it and destroy it permanently. Using the example of uranium, which is mined in Canada for both civilian and military purposes, the filmmaker addresses the global dimension of the capitalist-patriarchal system.

At the beginning of the video, there is a scene in which one of these mines is shown rom an overhead view. A controlled explosion sets off and runs through the mine. And then the image stops. The explosion starts again, but runs backwards. The environment remains destroyed before and during the explosion, but the montage points towards the possibility of changing the world as it is. The hopeful ending of the video ties onto this possibility, in which the filmmaker, despite his doubts, takes action to raise and care for an indigenous child.

From the perceptible to the construction of the truth: In Maxim Frank's video work History Cycle, the eye glides over high-resolution scans of everyday objects that are segmented and dissolving (such as soggy cornflakes), while, to the light rhythm of music a voice-over enumerates irritating facts: 49% of us would replace sunlight with moonlight if we could. It is estimated that 10% of our documents have a fake date on them. The most frequently lost item is a folder of paper. Televisions are getting smaller and smaller. But their ability to give off heat is growing by as much as 10% per year.

The interspersed assurances that these facts are true increase doubt about their accuracy. But how are facts created? Why do we rely on statistics to make sense of the world? In History Cycle, these questions are not answered, but the absurdity of the supposedly objective, directs our gaze to everyday objects and allows us to perceive them.

In White Pearl by Alice Escher, the future, the possible appears in the images of the old world. We follow voices and found footage through a tour de force of reflections, objectifications and desires. A motif that reoccurs in the dialogues and the images, is that of the external and internal world. The video illustrates these boundaries: The water glass that encloses moths and flies, a window pane that keeps out the storm, shots of an aquarium, with people on this side and the other, a snow globe, a conservatory, nuclear-family homes, the view from a bus. "The window pane keeps the outside world from crushing my arteries." Feeling secure, but not dissolving into it. Over the course of the video work, the motif of the spaceship develops. The spaceship as a container, as a total institution ("I am your grave"), as the conscious voice of a sex doll torso stylized into the brutally grotesque, distancing itself from the world. The themes change, to aging and gravity, the voices themselves more mechanical, repetitive, looping: "We're 97% identical." And as the containers become more precarious, older, rustier, the possibility of their emancipation is formulated: "The first name she received from her engineer. The second name she received from herself."

An Impossible Allegory by Matthew Arthur Williams begins with a clip of a photograph showing two men standing very close to each other, their bodies touching. Writing fades in, the beginning of a poem: I am collecting the

pieces / left in time / pieces that are not mine. The words of the American poet R. Nemo Hill become the words of the artist.

The following montage of images sings of closeness and touch: hands stroking over tulle fabric, arms holding each other, feet walking on sand, hands caressing one's own torso. The sound as well creates closeness: we hear the crackling that tulle makes when it is touched, the overdrive of the recording device that the wind brushes, scraps of conversation. On a third level, there is the poem, its lines fading in, repeating themselves. How does smell change a space? What remains when a love is lost? An Impossible Allegory answers: Closeness cannot be archived, it is practice, is body, is hand, is foot, is touch, is being touched, is collecting and looking and listening.

Paravent is the first exhibition in the program Failure, Futures, Fabrications in the community space of the collective 2o46 e.V. at Teilestr. 11-16.

Supported by the Fonds Soziokultur with funds from the Federal Government Commissioner for Culture and Media within the framework of NEUSTART KULTUR.

Text: Cornelia Herfurtner